Basel III Capital Floor Technical Note

Backgrounder -

Notice

A Statement from the Superintendent of Financial Institutions on the Basel III standardized capital floor level was issued on February 12, 2025.

1. Introduction

As a follow up to the regulatory notice released on July 5, 2024, this technical note presents additional information about the Basel III capital floor. This note touches on the following key points:

- Capital floors are not new as part of the 2017 Basel III reforms - indeed, capital floors were included in earlier Basel capital frameworks.

- Capital floors have multiple purposes, including: (i) reducing procyclicality of capital requirements; (ii) reducing excessive variability in risk-weighted assets (RWA) across banks; and (iii) promoting competition amongst Canadian banks.

- Basel III reforms comprise a suite of changes, some of which resulted in RWA declines (less capital required) and others - such as the adoption of the phased-in capital floor - resulting in RWA increases (more capital required).

- The changes that resulted in RWA declines have already happened (in Q2 2023) while the changes resulting in RWA increases are being phased-in over time. The overall impact of 2017 Basel III reforms for Canadian banks in totality is, per our calculations, broadly capital neutral. We present details of the increasing and decreasing elements of Basel III below.

2. Background

Our mandate includes promoting financial stability by protecting depositors and other creditors from undue losses. This is done by, amongst other things, ensuring that banks hold sufficient capital to withstand losses. The capital requirements for banks are outlined in the Capital Adequacy Requirements (CAR) Guideline. These requirements are largely based on the internationally agreed framework developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), commonly referred to as the Basel Framework, with adjustments made to reflect the Canadian context. Under the Basel Framework, risk-based capital requirements are set as a percentage of RWA.

The most recent update to the Basel Framework is commonly referred to as the 2017 Basel III reforms. Adoption of the 2017 Basel III reforms has been uneven across countries and has generated significant interest from bank analysts, economists, and the financial media.

3. History of capital floors in Canada

The capital floor (also referred to as the Basel III output floor in its latest form) that was included as part of our implementation of the 2017 Basel III reforms in Q2 2023 is a continuation of similar floors based on Standardized Approaches (SAs) that have been in place since 2008 when we began permitting banks to use internal models to determine capital requirements. The table in the Annex A compares the different iterations of the capital floor, its components, and the level at which they were set.

4. Purpose of the capital floor

The purpose of the floor is three-fold:

- to reduce pro-cyclicality of model-based capital requirements,

- to reduce excessive RWA variability and protect against model risk, and

- to promote competition amongst Canadian banks.

(i) Reducing pro-cyclicality of model-based capital requirements

Modelled requirements, calculated using the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach, incorporate a bank's own historic actual losses as a key factor in determining RWA. The use of historic data, however, injects an element of pro-cyclicality into IRB RWA calculations; in essence, holding everything else equal, periods of low loan losses result in lower RWA and periods of higher losses drive risk weights (RWs) higher.

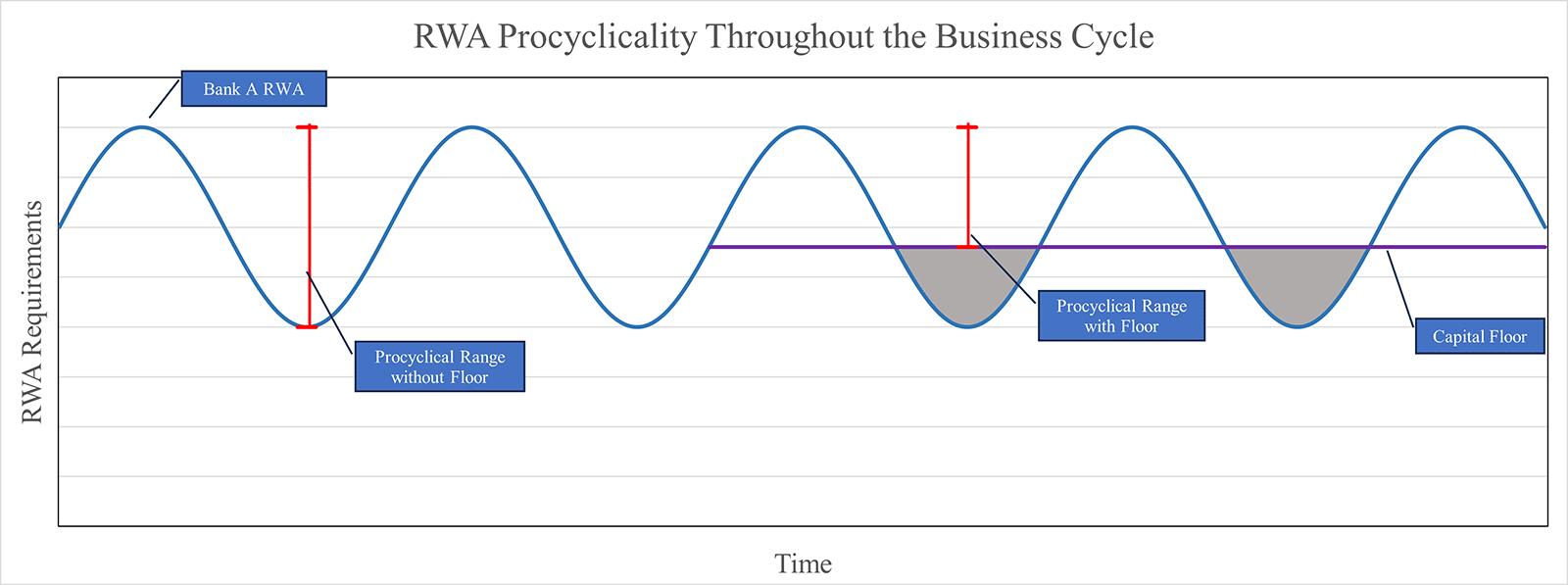

In a severe economic downturn, IRB requirements would rise, which, when combined with broader fears about credit quality and economic uncertainty, could result in banks constraining lending. A binding floor reduces this pro-cyclicality, lessening the increase in capital requirements in a downturn, which increases banks' ability to lend relative to the absence of a floor. Chart 1 below presents an example of how pro-cyclicality is reduced with a binding capital floor.

Chart 1 - Text version

Line graph showing how the capital floor reduces procyclicality in RWA requirements. The change in RWA requirements is plotted on the Y axis against time on the X axis. In this stylized example, RWA requirements vary over time. The gap between the peak and trough of the RWA requirements is shown to reduce from 4 units without the capital floor to less than 2.5 units when the capital floor is binding.

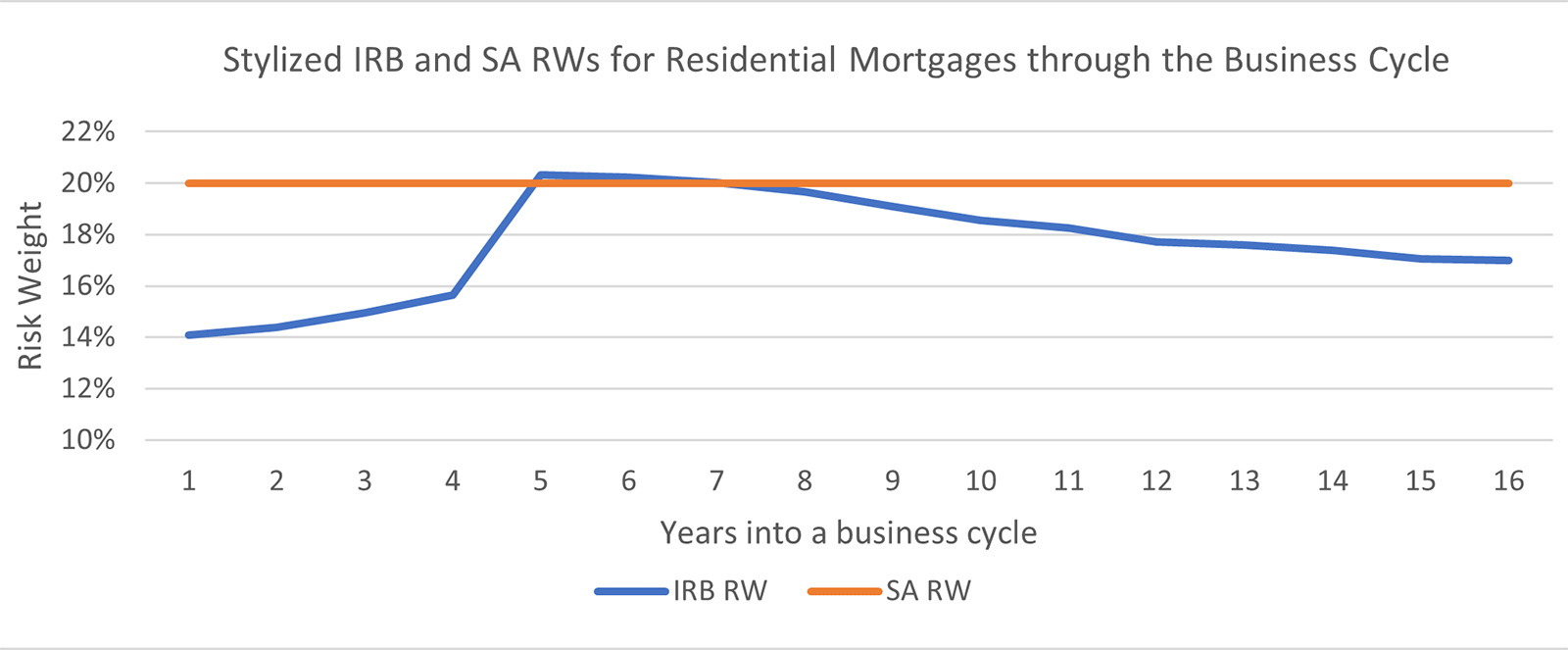

Chart 2 below depicts, via an illustrative example, how IRB RWs differ from the SA RWs; the latter of which are used to derive the capital floor.

Chart 2 - Text version

In this line graph, risk weights on the Y axis are plotted against the numbers of years into the economic cycle. It shows a flat orange line at a risk weight of 20% under the standardized approach and a blue line showing the IRB risk weights, ranging from 14% to just over 20%. The IRB risk weights are almost always lower than the SA risk weights, except at the peak of the stress at year 5 of the business cycle.

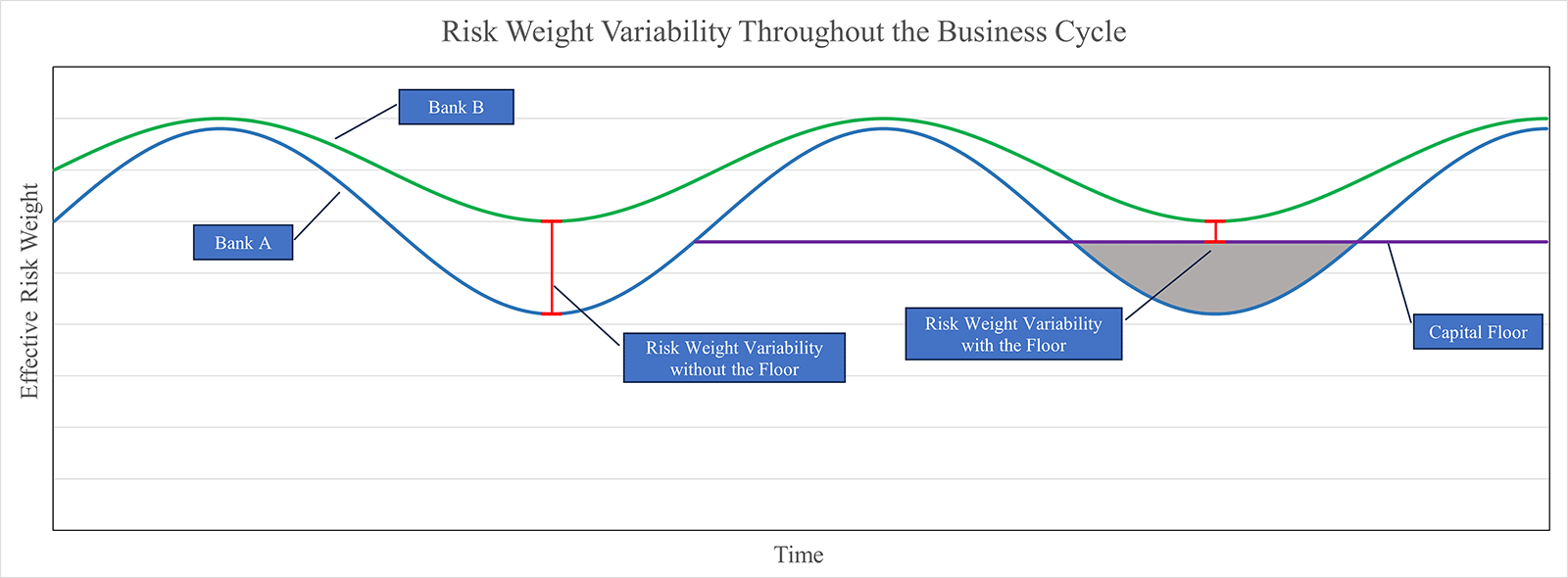

In addition, the capital floor helps to reduce RWA variability between banks as shown in chart 3.

Chart 3 - Text version

Line graph showing how the capital floor reduces variability in risk weights through a business cycle. The effective risk weight is plotted on the Y axis against time on the X axis. In this stylized example, the effective risk weight varies over time. The gap between the peak and trough of the effective risk weight is shown to reduce from roughly 1.8 units without the capital floor to roughly 0.4 units when the capital floor is binding.

(ii) Reducing excessive variability and protection against model risks

The capital floor also acts as a backstop to the modeled approaches. Capital floors protect against aggressive modeling behavior and provide a sound, credible cap on the maximum benefit banks can receive from the use of internal models for determining regulatory capital requirements.

Although the Basel III reforms were agreed upon in 2017, the need to protect against excessive variability and model risk has increased since 2020 given the distortion in data used for internal models from the significant fiscal support provided to business and individuals during the COVID pandemic. This support would have artificially lowered the number of defaults based on government support that should not be expected to occur in future economic downturns.

In addition, the BCBS observed a significant amount of RWA variability in modeled banks' portfoliosFootnote 1. The capital floor compensates for potentially significant amounts of RWA variability by ensuring that overall bank level RWAs do not drop below a certain level.

(iii) Promoting competition amongst Canadian banks

Lastly, the capital floor has the benefit of reducing the difference between capital requirements for banks using model-based approaches relative to banks using the SA. This should lead to more domestic competition, which ultimately benefits Canadian customers.

5. Implementation of Basel III and the capital floor in Canada

The 2017 Basel III reforms, along with the revised capital floor, were implemented in Canada in Q2 2023, with the capital floor starting at a level of 65% and transitioning up to 72.5% by Q1 2026. In July of this year, we announced a one-year delay of the planned increase of the capital floor from 67.5% to 70%, from 2025 to 2026, which delayed the fully transitioned capital floor at a level of 72.5% to Q1 2027.

We made the decision to delay the transition of the capital floor to give us time to consider the implementation timelines of the 2017 Basel III reforms in other jurisdictions. We continue to believe the capital floor is a prudent and useful tool as described above.

Overall, based on our estimates, the implementation of the 2017 Basel III reforms in Canada is expected to be capital neutral, even at the fully phased-in level of 72.5%. While there are many moving parts in the full suite of Basel III reforms, the two most impactful components of those reforms on bank capital levels were (i) the removal of the 1.06 scaling factor that was previously applied to modelled RWAFootnote 2; and (ii) the inclusion of the capital floor discussed above. According to public disclosures, aggregate modelled RWA of the domestic systemically important banks (DSIBs) was roughly $1,500Bn as of Q2 2024, which suggests the removal of the 1.06 scaling factor provides relief of roughly $90Bn in RWA (6% of 1,500Bn), ranging from $4.8Bn to $23.4Bn for the DSIBs.

Using information from DSIBs' Q2 2024 public disclosures, along with regulatory data publicly available on our website, we estimate the increase in RWA due to the fully phased-in capital floor to be approximately $85Bn. This has an impact on banks' Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratios ranging from 0 basis pointsFootnote 3 (bps) and 86 bps for the DSIBs. A detailed outline of our calculation of the capital floor can be found in Annex B.

Based on these calculations, the capital benefit from the removal of the 1.06 scaling factor is slightly greater than the aggregate impact of a 72.5% capital floor.

6. Banks have multiple different tools available to handle increases in capital requirements

While the implementation of the 2017 Basel III reforms as a whole is capital neutral, banks can choose to respond to increases in capital requirements due to the phase-in of the capital floor in several ways, including:

- Banks may make capital allocation decisions based on the changing capital requirements, which may result in balance sheet composition changing over time. We have observed this practice occurring over the last 15-20 years (see chart 4 below).

- Banks may transfer the risk of that exposure to third parties in order to free up capital.

- Banks may absorb any increases in capital requirements by maintaining a lower buffer relative to that bank's target capital ratio.

- As of Q2 2024, DSIBs had capital buffers relative to the Domestic Stability Buffer ranging from 127 bps to 191 bps, leaving them ample room to absorb the impact of the fully phased-in floor that ranges from 0 bps and 86 bps.

- Canadian banks have ample experience using the above tools, as well as capital generation from earnings, to manage temporal declines in capital ratios, including post-acquisition, without constraining business growth.

| 1990-2024 | 2001-2006 | 2007-2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total C$ assets | 6.5% | 8.0% | 4.9% |

| Non-mortgage loans | 6.7% | 8.6% | 6.6% |

| Mortgages | 8.6% | 7.2% | 8.2% |

|

Source: Statistics Canada, OSFI calculations. Table 10-10-0109-01 |

|||

Annex A - Comparison of the Capital Floor in Canada

Table 1 below presents the different iterations of the capital floor over time, its components, and the level at which the floor is set (floor factor).

| Basel III Output Floor | Interim Floor | Basel I floor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective years | Transition to 2027 | 2018-2023 | 2008-2018 |

| 1.06 scaling factor applied to model based RWA | No | Yes | Yes |

| Floor SA RWA for Credit Risk | Basel III | Basel II | Basel I |

| Floor SA RWA for Market Risk | Basel III | Basel I | Basel I |

| Floor SA RWA for Operational Risk | Basel III | None | None |

| Floor Factor | 72.5% | 70-75% | 90% |

Annex B

The calculation of the capital floor relies on the inputs listed in the first column of Table 2 below and produces each of the outputs according to the calculations listed in the second column. Each of the inputs can be found either in banks' public disclosures or in the regulatory data filings available on our websiteFootnote 4. Table 3 contains the calculation of the impact of the removal of the 1.06 scaling factor and the fully phased-in capital floor of 72.5% for the six DSIBs.

| Inputs and Outputs | Calculation details |

|---|---|

| Pre-floor RWA | A |

| All-SA RWA | B |

| Pre-floor net allowances in capital | C |

| Total Stage 1 and 2 Allowances | D |

| Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital | E |

| RWA add-on for floor | F = (72.5 ÷ 100) × (B − 12.5 × D) − (A − 12.5 × C) |

| RWA benefit of removal of 1.06 scaling factor | G = 0.06 × Modeled Credit Risk RWA |

| Net benefit of the floor and 1.06 scaling factor | H = G − F |

| Impact of 72.5% floor (bps CET1) | = 10,000 × ((E ÷ (A + F)) − (E ÷ A)) |

| Benefit of 1.06 scaling factor (bps CET1) | = 10,000 × ((E ÷ (A − G)) − (E ÷ A)) |

| Net benefit (bps CET1) | = 10,000 × ((E ÷ (A − H)) − (E ÷ A)) |

| BMO | BNS | CIBC | NBC | RBC | TD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-floor RWA | 418 | 450 | 327 | 136 | 654 | 603 |

| All-SA RWA | 633 | 694 | 492 | 200 | 965 | 865 |

| Pre-floor net allowances in capital | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Stage 1 and 2 Allowances | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital | 55 | 59 | 43 | 18 | 83 | 81 |

| RWA add-on for floor | 21 | 31 | 7 | 5 | 21 | - |

| RWA benefit of removal of 1.06 scaling factor | 14 | 12 | 14 | 5 | 21 | 23 |

| Net benefit of the floor and 1.06 scaling factor | (7) | (19) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 23 |

| Impact of 72.5% floor (bps CET1) | (63) | (86) | (29) | (42) | (40) | - |

| Benefit of 1.06 scaling factor (bps CET1) | 44 | 37 | 57 | 48 | 43 | 54 |

| Net benefit (bps CET1) | (23) | (54) | 26 | 2 | 1 | 54 |